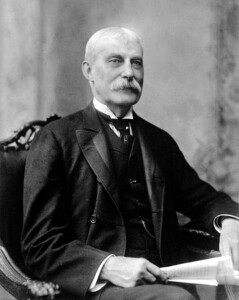

Henry Flagler: The Father of Modern-Day Florida

The influence of Henry Morrison Flagler will forever be felt around the state.

The Early Days

Considered the man who industrialized Florida, Henry Morrison Flagler is to the railroad industry as John D. Rockefeller is to the oil industry. In fact, the two were once in business together, as Flagler and Rockefeller founded Standard Oil in 1870.

The Flaglers lived in New York, but Henry’s first wife, Mary Harkness Flagler, was ill; they visited St. Augustine in 1878 following their doctor’s recommendation, hoping that the sunshine and sea air would help her respiratory ailment. Although Mrs. Flagler grew temporarily stronger, she died in 1881 after a return to New York.

Flagler later returned to St. Augustine in 1883 on a delayed honeymoon with his new wife, Ida Alice Shourds. He had been charmed by the city and its weather but frustrated by the lack of transportation and hotels. He envisioned Florida’s appeal to out-of-state visitors and decided to pour his oil fortune into its development.

The Rest is History

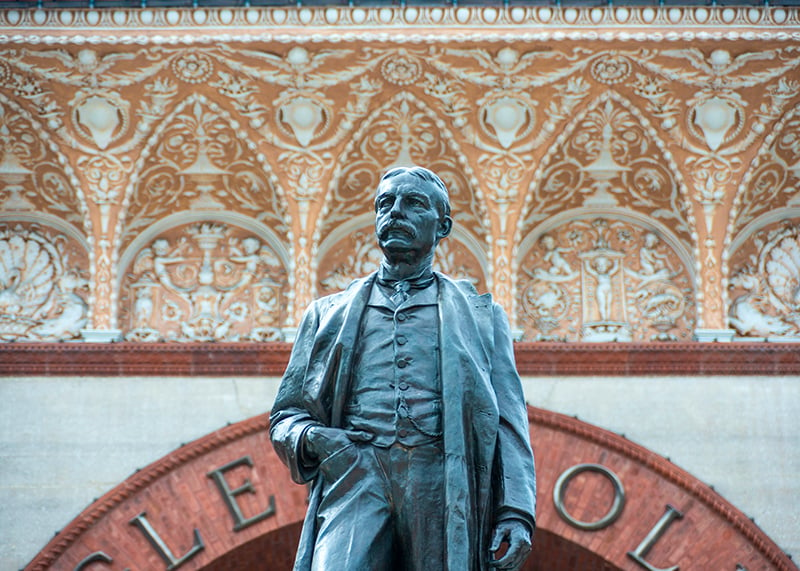

And a compelling history at that. Flagler put St. Augustine on the map with his 540-room Hotel Ponce de Leon (now Flagler College), an opulent Spanish Revival structure with signature windows by Louis Comfort Tiffany that still shine bright today. Then, Flagler set to work buying up existing railroads to start his railway system. Two years later, he built a railroad bridge across the St. Johns River and headed south.

Next up, West Palm Beach, Flagler’s intended end to his railway system. Deep freezes in 1894 and 1895 prompted landowner Julia Tuttle, an advocate of Florida development, to send Flagler a spray of orange blossoms as proof that the severe weather hadn’t reached southern Florida, an incentive to extend his railroad to Miami. She also offered Flagler land for laying tracks.

The Florida East Coast Railway pulled into Miami for the first time on April 13, 1896.

Population Explosion

The city of Miami was originally a small outpost named “Fort Dallas.” After Flagler’s and Tuttle’s hand in the railroad’s expansion, the population grew rapidly, from 260 in 1896 to more than 1,600 in 1900. In addition, Floridians who had previously been cut off from the rest of the state were now able to vacation in southern Florida.

In 1897, Flagler built the Royal Palm Hotel, overlooking Miami’s Biscayne Bay.

It featured the city’s first electric lights, elevators and swimming pool and was one of the first hotels in Miami. Tuttle helped the hotel secure an exemption to serve alcohol to its guests during the three-month tourist season, making it one of the city’s most popular destinations.

Flagler also provided Miami’s initial infrastructure by having a channel dredged, streets built and funding Miami’s first newspaper and water and power systems. He encouraged fruit farmers and other settlers to set up shop alongside his railroad line, and helped finance churches, schools and hospitals.

Upon its incorporation, the residents wanted to name the new city “Flagler” in appreciation of his contributions to the city. However, Flagler urged that it be called “Miami” after the Native American name for the river that ran through the city.

“Henry M. Flagler first built Standard Oil and then built the state of Florida. He may have been America’s most modest industrial titan—and its most underappreciated,” business and finance writer John Steele Gordon told Audacity Magazine in 1996. “Henry Flagler not only was present at the creation of the modern economic world but was one of its prime creators.”

In 1917, Florida honored Flagler by naming its 53rd county after him.

Decadence and Glamour

Being accustomed to the finer things in life elevated Flagler’s design aesthetic. He hired two young architects, John Carrère and Thomas Hastings, from New York to design Hotel Ponce de Leon; its prominence put them in the spotlight and allowed them to open their own high-powered firm. Interior designer Louis Comfort Tiffany’s sweeping style showcased grand murals, mosaics, terra cotta reliefs, and, of course, stained glass windows.

“With him it is never a case of ‘How much will it cost?’ Nor of ‘Will it pay’ … Permanence appeals to him more than to any other man I have ever met. He has often told me that he does not wish to keep on spending money for maintenance of way, but to build for all time,” said journalist Edwin Lefevre in Everybody’s Magazine, February 1910.

Hotel Ponce de Leon was St. Augustine’s first large-scale structure built entirely with concrete, and directly influenced southern Florida’s architecture for many years to come. Although St. Augustine never caught on as a resort destination in the early 20th century, Hotel Ponce de Leon was one of only three Flagler hotels to survive the Great Depression.

Hotel Alcazar was initially planned as Hotel Ponce de Leon’s entertainment corridor. Posh inside and out, the Alcazar was known for its facilities, which included Turkish and Russian steam baths, cold plunge pools and massage rooms. The four-story complex ended in a grand casino that housed the world’s largest swimming pool (at the time), right in the heart of the casino.

Alcazar also had an archery range, bowling alley, tennis courts and a croquet lawn.

Flagler also purchased and renovated two hotels in St. Augustine, one of which still stands today. He purchased the Hotel Casa Monica from abolitionist Franklin W. Smith and renamed it Hotel Cordova. The hotel not only became iconic for its Moorish architecture but as a meeting place for the glitterati. It was restored to the Casa Monica after hotelier Richard Kessler purchased it from the St. Johns County government in 1997.

Palm Beach would see an even more decadent take on the destination hotel. Considered a winter playground for America’s richest travelers, guests of the Hotel Royal Poinciana (which opened in 1894) could take their own private railway cars directly to the hotel’s entrance. An orchestra played daily in the hotel pavilion, and guides regularly took guests on fishing expeditions in the Atlantic Ocean. Pedi-cabs transported guests along the hotel’s three miles of hallways.

Then came The Breakers, first known as the Palm Beach Inn, in 1986. This simple, unpretentious resort that overlooked the ocean caught fire during an expansion project; when rebuilt as The Breakers, its register regularly featured names such as Andrew Carnegie, J.P. Morgan and the Vanderbilts.

Fire struck once again in 1925; the subsequent rebuilding saw The Breakers the world knows today. Inspired by the Villa Medici in Rome, the property offers a private beach, four oceanfront pools, complimentary chauffeured Tesla house car service and many other luxurious amenities.

The Venture Further South

Flagler also had his sights set on Key West. When the U.S. began building the Panama Canal in 1905, Flagler envisioned a major commerce hub, and decided to extend his railroad to Key West. This required adding 156 miles of track, most of it over water.

The project, known as “Flagler’s Folly” during construction, wasn’t an easy one. Flagler’s team battled rough weather from three major hurricanes, and in 1906 had to halt construction for a year.

The railroad was completed in 1912, shortly after Flagler’s 82nd birthday. It later would be known as “The Eighth Wonder of the World,” and was destroyed by a hurricane in 1935.

Former U.S. Secretary of State Elihu Root described the project as “…second only to the Panama Canal in its political and commercial importance to the United States.”

Flagler’s Influence Today

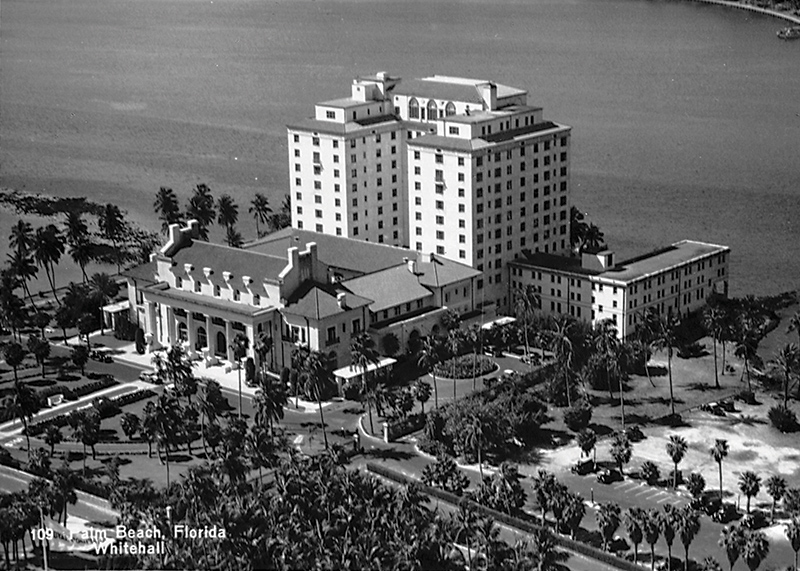

Flagler died from injuries he sustained falling down a staircase at his estate, Whitehall (now the Flagler Museum) in 1913. He was instrumental in the development of Florida’s leading industries, agriculture and tourism, and put Palm Beach on the map as one of the world’s most coveted winter destinations. The true reach of his influence is inestimable.

A National Historic Landmark, the Flagler Museum preserves Whitehall as it appeared during Flagler’s lifetime. In 1905, the New York Herald proclaimed that Whitehall “was more wonderful than any palace in Europe, grander and more magnificent than any other private dwelling in the world.” Its 75 rooms encompass 100,000 square feet and were designed in historic styles such as Louis XIV, Louis XV, Louis XVI, Francis I and the Italian Renaissance, typical of Gilded Age mansions of the day.

The museum’s pièce de résistance is Railcar No. 91, built in 1886 for Flagler’s private use. Both its interior and exterior have been restored to its 1912 appearance, when Flagler used it to ride his rails from St. Augustine to Key West.

Flagler in Florida

Casa Monica Resort & Spa

(formerly Hotel Cordova)

95 Cordova St., St. Augustine

904.827.1888

Flagler College

(formerly Hotel Ponce de Leon)

74 King St., St. Augustine

904.819.6220

Lightner Museum

(formerly Hotel Alcazar)

75 King St., St. Augustine

904.824.2874

1 S. County Road, Palm Beach

561.655.6611

One Whitehall Way, Palm Beach

561.655.2833

1545 Collins Ave., Miami Beach

305.604.5700

“Flagler’s Folly” Pigeon Key Visitors Center

2010 Overseas Highway, Marathon

305.743.5999